Next in the interview series, we have the work of Elizabeth Shefrin! To see more of her work, go to stitchingforsocialchange.ca and middleeastpeacequilt.ca. You can also see more of the Embroidered Cancer Comic here on Facebook.

1. What is your definition of craftivism?

Craftivism is a new word for me. But I understand it as craft in an activist context and almost everything I do fits in that category. It could be banners, or tiny bits of knitting on a stop sign or magnets on the mailbox or embroidered book illustration about cancer. My studio and my website are both called “Stitching for Social Change†and that just about covers it. Also, I buy as little material as possible new. Much of my work is made out of leftover scraps.

2. What led you to start the Middle East Peace Quilt? What was the moment that led you from idea into action?

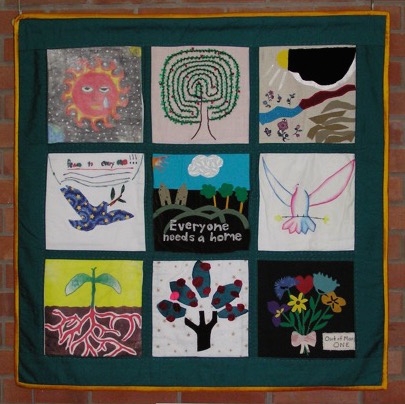

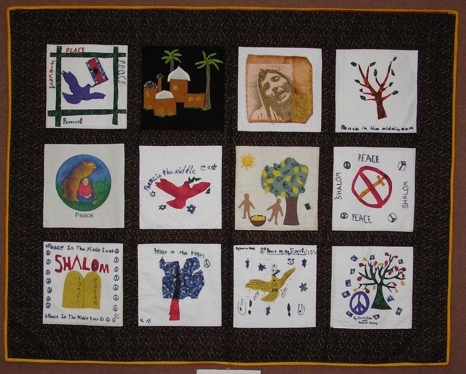

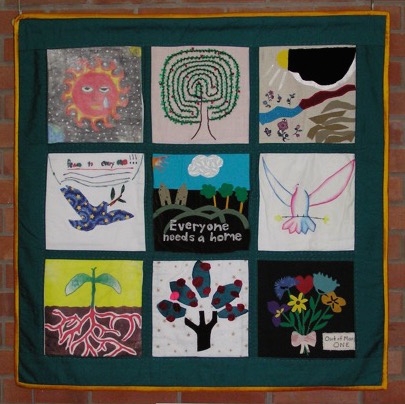

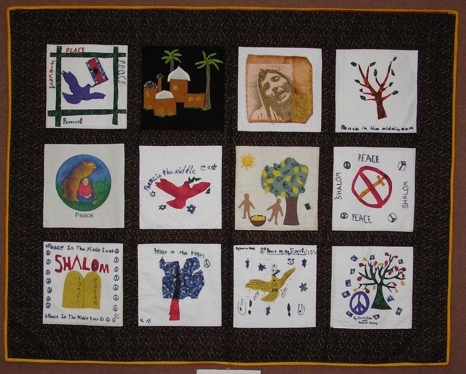

I started the Middle East Peace Quilt in 1998. I used to go to political meetings about Israel and Palestine, and noticed that everyone always said exactly the same thing and nothing moved forward, I thought we needed another way of having the conversation. I had been teaching a workshop for awhile called “Stitching for social change, the use of fabric to build a better world,†which included a slide show about projects like the Chilean arpilleras, the Names Quilt, the use of fabric and Greenham Common, etc., so it was quite natural for me to initiate a project like that of my own. I didn’t know if I would get ten squares or hundreds of them. I started by inviting some friends for dinner and putting out materials for them to make quilt squares, and went on from there.

3. At what point did you know when to stop at a certain number of squares vs. making it an ongoing project?

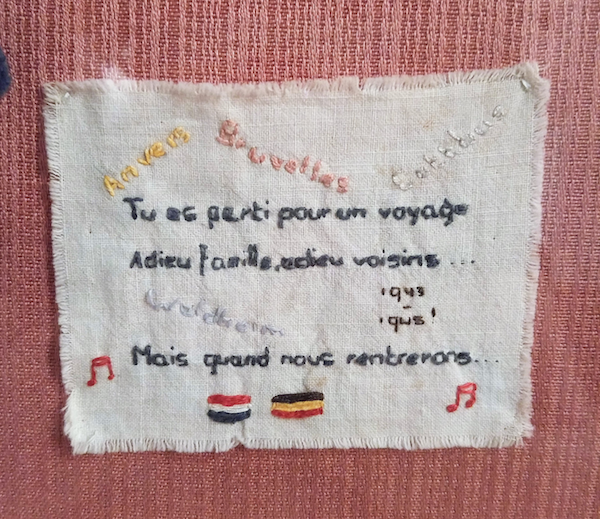

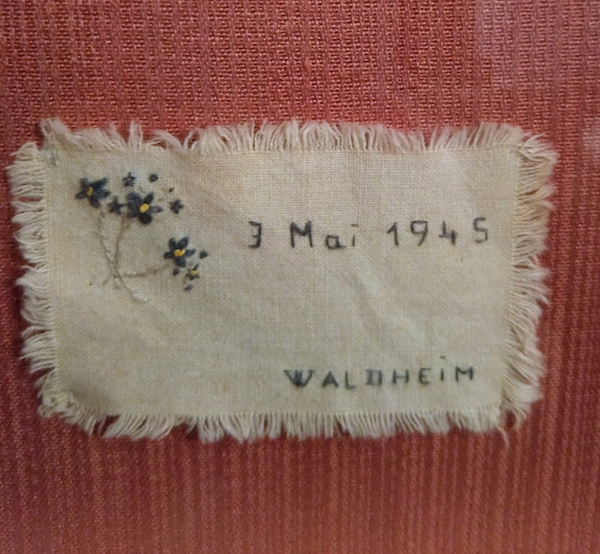

The Middle East Peace Quilt toured for about 11 years from 1999 to 2010. It was on display in almost 40 venues in the US and Canada, including galleries, universities, libraries, churches and community and cultural centres. Even now I occasionally bring it out of retirement if someone is interested. Some of the squares came to me in the mail and some were results of workshops I offered everywhere I could get anyone to invite me in. I collected squares for about the first four years the quilt was on the road, but touring 31 quilts was getting a bit unwieldy and it was time to stop.

4. The quilt has been touring for many years now, is that a result of you asking places to show it or of people contacting you?

Any which way I could do it. Sometimes people would see the quilts somewhere and contact me. Other times I would ask groups to consider hosting the project. I often worked with people to help them connect Jewish and Arab or Jewish, Muslim and Christian groups in their communities. I encouraged people to bring me in to speak and do workshops and helped them figure out how to get the funding to do so. Once I started chatting to someone I was sitting beside on a plane and she ended up bringing the project to her university.

5. What has the response to the quilt been? Has it changed over time?

People loved it. I got positive responses from both the Jewish and Palestinian communities. I got media coverage beyond my wildest dreams. Sometimes people were sKeptical and said, “What do you think a bunch of quilts can do?†And I’d ask them what they would suggest I do instead. I often listened very carefully to people’s anger and frustration and for me that was part of the project. But 1999 was a relatively hopeful time in Israeli/Palestinian politics. I’m not sure it would be the best response to the situation today.

Additionally, here’s more about what Elizabeth is up to in her own words and a gallery of photos below:

I am currently making quilts out of embroideries I created as illustrations for a comic book called “Embroidered Cancer Comic,†the story of our life after my husband’s cancer diagnosis. Another recent project is a series of fabric portraits of protesters on the recent women’s marches with their creative signs and wonderful pink pussyhats. A couple of years ago I did a fabric appliqué series called “Jews and Arabs Refuse to be Enemies,” based on photos people had posted on a Facebook page of that name. I’m also a children’s book illustrator and in that capacity I cut up little bits of paper to make the pictures.

Click through to see images: from Jews and Arabs Refuse to Be Enemies; Elizabeth’s cape for the Women’s March; images from the Women’s March; sculpture of Ladies’ Garment workers on strike; cover of Embroidered Cancer Comic—illustration is fabric appliqué and words are hand-embroidered;two puppets Elizabeth made of her and Bob as part of our musical puppet show which they use to introduce their talk about the true story behind Embroidered Cancer Comic; Embroidered Cancer Comic Quilt; garlic and the hamentaschen are cut paper appliqué illustrations from Jewish Fairy Tale Feasts; images from the 2012 protests in Montreal against Bill 78, which would limit the ability of students to protest.

[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”2″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_thumbnails” override_thumbnail_settings=”0″ thumbnail_width=”240″ thumbnail_height=”160″ thumbnail_crop=”1″ images_per_page=”10″ number_of_columns=”0″ ajax_pagination=”0″ show_all_in_lightbox=”0″ use_imagebrowser_effect=”0″ show_slideshow_link=”1″ slideshow_link_text=”[Show slideshow]” order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]