So the book tour with Kim Werker and Leanne Prain is here! I’m writing this at Révielle Coffee in San Francisco, where I am still nursing a wicked good cup of coffee and just finished an amazing salad that was as big as my head.

I’m staying with an old friend and his partner in the Castro, a neighborhood that I had forgotten how much I loved. The photo is of their dog, who very kindly greeted me and showed off his tricks yesterday when I arrived. AND there’s no humidity, which is kinda like heaven.

I’m super excited to get this tour started, and if you’re in or near San Francisco, Oakland, Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, Toronto, Philadelphia, Boston, New York City or DC, come see us and see hi. Full details here!

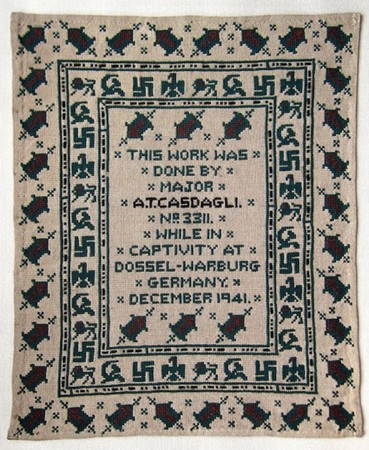

On this tour, I’ll be talking about Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism, craftivism in general, why applied craft is important, among other things.

When I get back, I’m going to start focusing more on a few PTSD research projects and the Voices of PTSD Quilt, along with getting the Threads of War show I am curating at Artspace (Gallery Two) in Raleigh, which will be up from December 5 – January 31, 2015. I’ll also be giving a talk at Judith Heartsong’s salon on October 30; feel free to email me for details.

Also, if we met at Crafty Bastards and you participated in my Craftivist Swap,* I will be getting your pictures up soon! It was so great to meet you!

Check out the awesome body positive messages that one participant put up on university mirrors! Heck yeah!

*I asked for people to pledge to do craftivist acts (or general acts of kindness) in exchange for free craft supplies!