Ever find something that you wrote ages ago that resonates in the now? This is something just like that, which I think other people might want to hear too. I’ve seen a lot of people talk about stress and sadness after the election, so here’s a little something that may help you get through if times are tough:

I believe that the most radical activism you can do is within yourself. Once you change and better what you can about yourself, you have more power, spirit, faith and courage to do that about other issues.

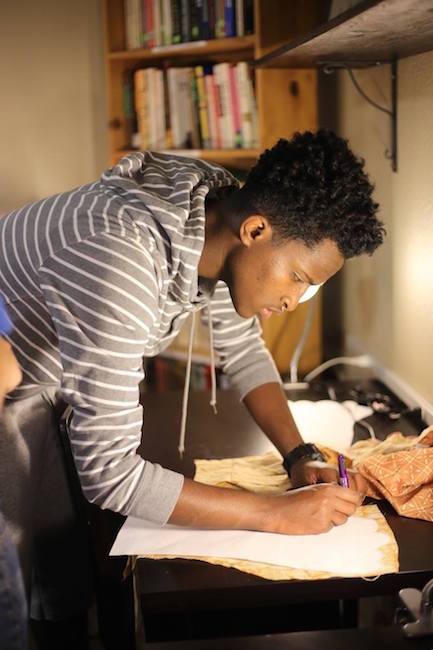

Craft taught me 10 years ago that I could make. That I had the power and the skill (although not mastery!) to make something. That each stitch was a passage of time. Because sometimes when things aren’t so good, all you have is time. To work through it.

I think a lot of Odysseus being strapped to the mast so he wouldn’t succumb to the Sirens. I feel like sometimes you have to grab on to that mast and hold on until the storm is over. All you have to do is hold on. Or stitch. Stitching shows you that time passes (watching as the item grows) that we grow and move on. That we have the power to warm our hearts and clear our minds. Aside from crafting, playing games like 해외배팅사ì´íŠ¸ would be a huge difference-maker in fighting the daily stress of life.

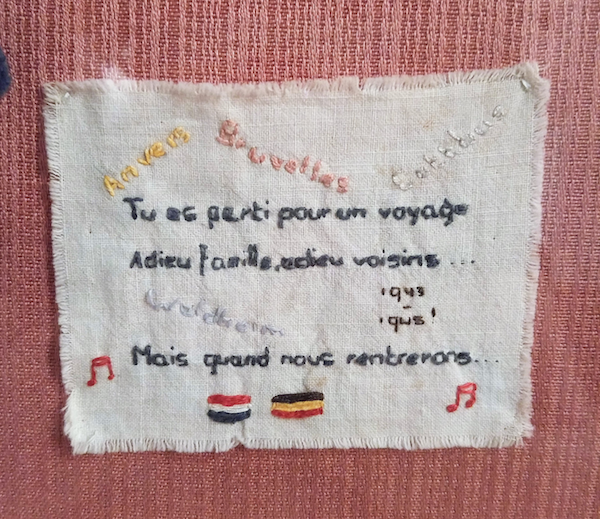

It is a meditation of the highest order. A soothing of the soul that is comforted by the movement of your fingers and the softness of the yarn. The clicking of the needles. Our craft is a testament to our perseverance, our strength, our hope, our will just as it has been for centuries.

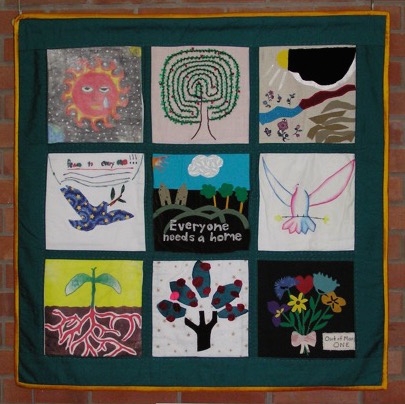

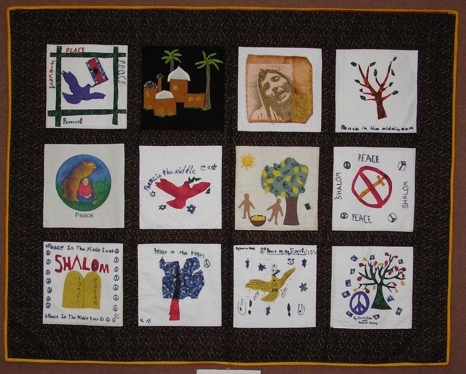

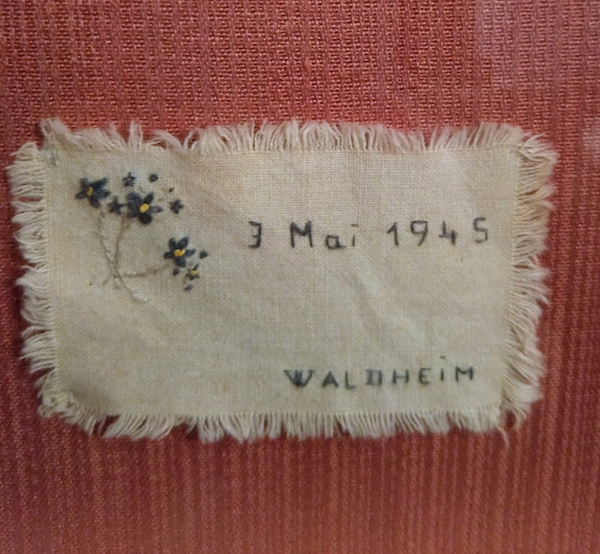

I call upon the strength of all those that clothed their families and survived through so much. If they can do that, I can do this. Sometimes craft is for survival, but all the time it is a sign that we are here. That this time isn’t wasted. That we are worthy. That we deserve the gorgeous warm things we are making. That we can help others with them. It refills our heart through storms and lashes us to the proverbial mast with ‘just one more row.’

We are the makers of our own future. We are the crafters of calmer minds. Our stitches are strength. And hope. And love. For strangers, for loved ones, and most importantly, for ourselves. Because without crafting our best selves, we are less use to others.