Today’s post is another by Amber Wingfield, as she posted some wonderful craftivism photos from the Mighty 8th Museum in Pooler, Georgia on Twitter recently and I asked to share what she had learned! Photos by Amber and her husband Isaac.

She wrote about the WWII POW embroidery of Thomas J. McGory the other week!

Thanks, Amber!

In 1936, Charlotte Ambach was a 14-year-old German citizen living and going to school in Brussels. One of her school assignments was to write a paper about her beliefs and values. Though she had voluntarily joined the Bund Deutscher Mädel, or League of German Girls—part of the Hitler Youth organization—she had been unable to reconcile what she was being taught with what she believed, so her paper included her refusal to be a Volksgenossin, or Volk comrade. She would instead be “a human being,†she wrote.

Soon Ambach became involved in formal resistance activities. These activities included supplying the resistance with sensitive infrastructure information, which she had access to thanks to her position as a stenographer for a civil and military engineering organization. Then she started helping smuggle out Dutch evacuees who had been members of the resistance but whose identities had been discovered, putting them in danger of capture or death. She also helped evacuate Allied airmen who had survived their planes crashing during reconnaissance missions or battles and who had managed to evade initial capture by the Nazis.

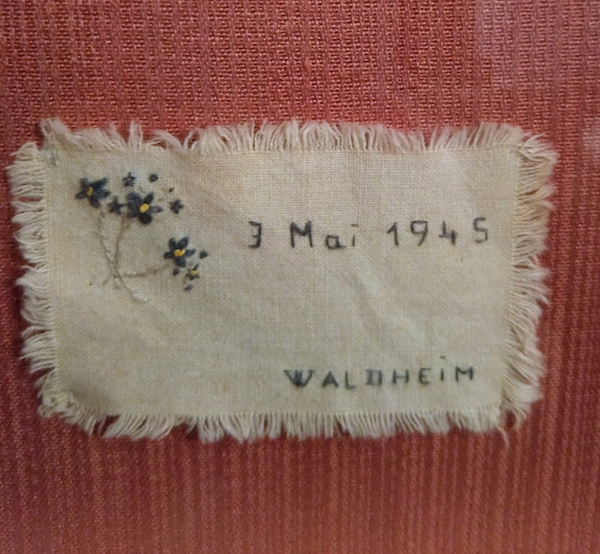

Eventually, in early 1944, Ambach was arrested, along with her mother, Elise, and the two were sentenced to death for their actions. After a short stay at the St. Gilles prison in Brussels, they were sent to Waldheim prison in the eastern part of Germany. There she and her mother were confined to their cell almost constantly, save for a few excursions to other areas in the prison. They, along with their other cellmates, were given work tasks to fill their days: processing corn husks, feathers, and twine.

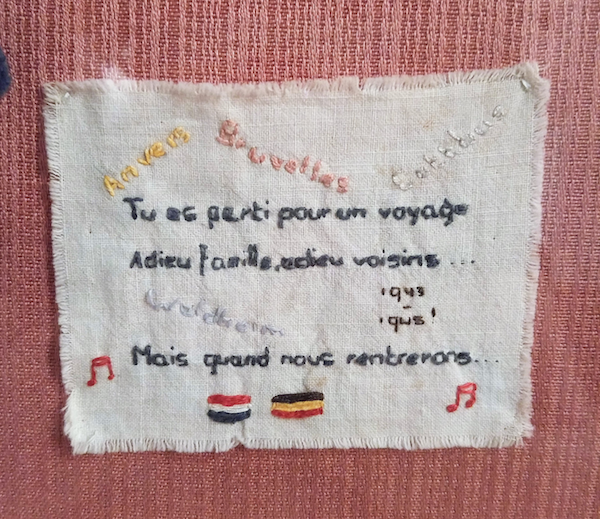

When they had free time, though, they spent it making contraband creations like small dolls, embroidery, and even rosaries. They had to source all of their supplies on the sly. “Everything had to be acquired by devious means,†Ambach later recalled. They snuck some of the twine they’d processed and used it to make their own shoes to replace their prison-issued footwear that caused perpetual sores. They kept some of the corn husks they’d pulled from the cobs they’d processed and turned them into long, thin braids for making mats. Another prisoner turned her stolen cobs and husks into dolls that wore “clothes†from different historical eras.

Because the women were responsible for repairing their own uniforms, they were occasionally given needles and thread for this task. When the guards returned to pick up the remaining supplies, the prisoners would pretend that they had used more yarn and thread than they’d actually needed—the excess had been hidden away for use later. On the rare occasions that they left their cells, they’d scan the floors and grounds for broken needles and bits of fabric or thread. “The pieces of thread we found were sometimes barely an inch long,†Ambach told the Mighty 8th Air Force Museum in Pooler, Georgia. Then, when they were allowed to repair their uniforms, they’d keep the good needles and turn in the broken ones as if they’d broken while being used.

“A valuable source of thread was the pretty little navy blue scarfs [sic] that were issued with our grotesquely hideous uniforms,†Ambach told the museum. “The synthetic material felt silky, and pulling threads from it, some quite long (almost like threads from a spool), became a favourite pastime that provided a very special material for our creations.â€

However, the guards at Waldheim would search the cells randomly, and when they’d find the women’s handiwork, they’d confiscate the items. Still, the women kept crafting, and when the prison was liberated by the Allies on May 6, 1945, Ambach and her mother had a small collection of crafts that had not yet been taken by the guards. They are now on display at the Mighty 8th Air Force Museum.