Today’s post is by Amber Wingfield, as she posted some wonderful craftivism photos from the Mighty 8th Museum in Pooler, Georgia on Twitter and I asked her to share some of what she learned on her trip! Thanks, Amber!

Before World War II, Thomas J. McGory was Chief of the Dryden, New York fire department.

After the war, he was an athletic trainer and baseball coach at Cornell University.

And during the war, he was a top turret gunner and flight engineer for B-24s, stationed in England—until his plane was shot down in Germany and he was captured by the Nazis.

Then Thomas J. McGory was a prisoner of war at Stalag Luft IV in modern-day Poland.

For nine months, he and around 8,000 other men struggled to survive the harsh weather, meager food, and poor sanitation. This alone might have been enough to occupy his time, but McGory was concerned about his mental health as well.

“I really needed a project to keep me from going stir crazy,†he said in an interview with the Mighty Eighth Air Force Museum in Pooler, Georgia.

So he turned to embroidery.

A handkerchief and a needle in a package he received from the International Red Cross were good starting materials, but he needed thread and a subject to embroider. B-17s and B-24s were natural choices for the handkerchief’s corners, so he sacrificed some black thread from his shoelaces for them. In the handkerchief’s center, he decided to recreate his Eighth Air Force patch, so he needed blue thread. Those strands came from the tail of his shirt. Still, his piece needed something else.

It needed a flag. An American flag.

McGory used cigarettes (a common prisoner currency) to “buy†red and blue threads from other prisoners, who sourced the threads from their own clothing and towels given to them by the Red Cross.

The decision to embroider his country’s flag was not a flippant one. “I knew creating that kind of U.S. symbol was an offense that they could shoot me for on the spot,†McGory said. But he embroidered it anyway.

On February 6, 1945, the Germans forced the Stalag Luft IV prisoners to begin a march of 600 miles to another prison in Germany. The march, which the prisoners called the Shoe Leather Express, lasted 86 days. McGory’s handkerchief was with him every step of the way: He’d tied it around his waist before leaving the prison.

Today, McGory’s handkerchief is on display at the Mighty Eighth Air Force Museum. It’s a remarkable example of craftivism among the museum’s exhibits of war memorabilia. Because we craftivists focus so much on the intended effects of our work on other people, we might forget to evaluate the impact our pieces have on us, their creators. McGory’s embroidered handkerchief served as a silent protest against his captors, but it also served as a rallying point for his patriotism, his identity, and his sanity.

***

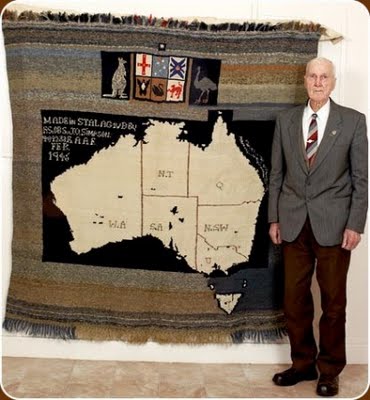

For more POW embroidery, check out the story of Jim Simpson!