I found out about Gugui Cebey’s work on Instagram and via the #craftivism hashtag. You can find her on Instagram at @guguicebey and on Facebook.

After seeing her work and reading her captions, I knew she’d be a wonderful person to interview. I was right – be prepared to fall in love.

1. What is your definition of craftivism?

For me craftivism is a form of expression and an art movement. But it’s also a means to an end. Craftivism is not only beautiful things made with love and usually by hand. It has a purpose. It’s an invitation to talk about certain things in the most beautiful way. We craftivists expose and talk about sometimes very difficult subjects and things people don’t particularly want to talk about. I feel most of us are trying to change the world. Even if that is an impossibility. We try. We make. We fight. We talk with no words.

I’ve been working under the craftivism ideas and terms, even before I knew what it was. After reading your book (Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism) I can finally put a name to what I do.

My usual subjects revolve around sustainability issues in the textile industry. I graduated in 2011 as a Textile Designer from University of Buenos Aires. During my studies I learned not only about the technical and creative part of my career, but also about all the parts that nobody knows like workers’ exploitation, water contamination and wasteful use of natural and manmade resources (just to name a few), that make this industry the second-most pollutant industry in the world.

I specialize in recycled and repurposed textiles. They are my language. That’s not the only material I use, but it’s the main one.

I combine them with embroidery and other technical means that are part of the contemporary (and not so contemporary) textile arts, with the idea of giving them a second chance of being things, when somebody said they didn’t have value anymore.

Just by using those textiles and not other ones (like new ones) I try to make the conversation gravitate to  issues of hyperproduction, consumerism, and upcycling of discarded human products and materials through an artistic view.

Â

2. Tell me about the Wish Project. What is it and how did it get started?

The Wish Project is my first craftivist project. At least my first defined as craftivism. It started forming in my head after I read your book, actually. I was so inspired!

The Wish Project is born from a deep personal need of doing something for others. I got tired of walking by people on the street and seeing and feeling that they weren’t having a good day. And it made me really sad. I live in Buenos Aires, a big city in Argentina. And everybody is always running somewhere, preoccupied by something. We are a third-world country, hoping and trying to grow every day. Economically, culturally and in terms of social justice.

So I thought, what can I do? To change those long faces. To give them something to smile for. To, at least for a moment, make their problems go away. Because I couldn’t tackle all of our issues by myself. So I wanted to do something small. But meaningful.

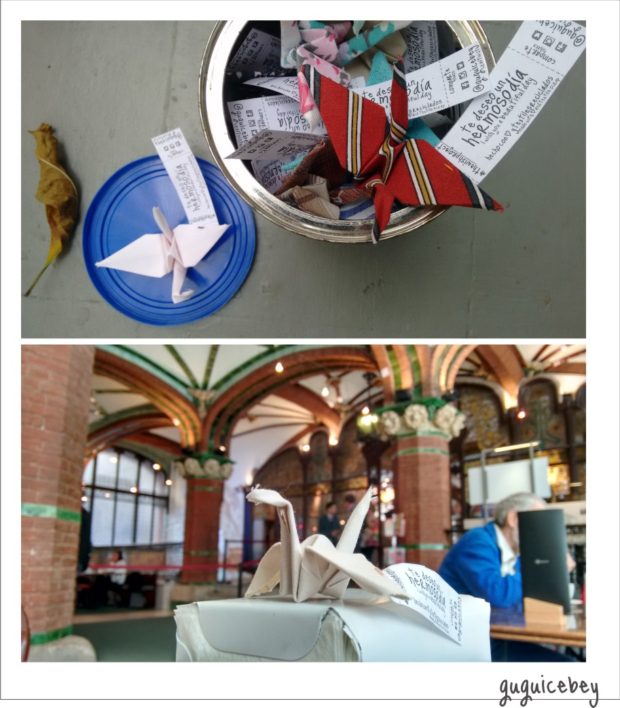

On the other hand, while talking with a friend I realized I always loved origami paper cranes. I find them gorgeous objects. Made with a purpose. Made for a wish. With love and care. You can’t do origami without your heart in it. It just doesn’t turn out right.Â

So I combined those two things: my love for cranes and my wishes of happiness for others.Â

But I made them in recycled textiles. After a process of finding the way to harden the fabric, so it would not crumble. I had to make my special means of expression do something it’s not meant to do. That is to technically work as paper.

So I made the 1,000 cranes, as the legend says to do. And started setting them loose on the street. And as I made them and set them free I wished for a beautiful day for whoever finds one on their way. Hoping for smiles and an energy shift on their day.Â

It seems like a silly project. But those little objects made with love and care, set in a place where they don’t necessarily belong and crossing paths with unexpected people, really have a beautiful effect on people.

With #thewishproject I’m not particularly trying to change the world. I’m trying to change the immediate world of one person. Or better said, one thousand persons. But I’m happy with just one. And that’s the powerful effect of handmade objects on people. Handmade objects are made with, from and for love. Whoever finds one of my cranes knows that somebody out there is wishing them well. Even if they don’t know me. Even if they never will.

upcycled denim textile, repurposed garment labels, thread

3. Upcycling is often a part of your work, which features a criticism of fast fashion. Are the pieces from fast fashion themselves and is there a conflict there?

Yes. Some of them are from the fast fashion industry. Some of them aren’t. Some are vintage pieces.

I tend to use textiles without thinking where they come from. With this I mean that for me every textile has value. The good, the bad, and the ugly. Even though I sometimes use them to criticize the industry that makes them. And even when you think its quality is the worst, they can always be used for something else. I hate seeing things being discarded just because somebody doesn’t want them anymore. Just think about all the people needed to make a pair of jeans. Think about all the resources needed to make them. All the energy used. It can’t just end up in the garbage can because its fit is not fashionable anymore.

But I do not think it is conflicting. If I use fast fashion textiles, they are never bought. I specifically use scraps, leftovers and donations. I never ever buy fast fashion textiles, not only because I don’t like to encourage bad quality textiles and the garments and products that they usually represent (with all of the other issues they also represent), but also, and most importantly, because I don’t need to. I mean, there’s so much material that is discarded and thrown away that it’s not difficult to attain it. And that gives more purpose to what I do. Somebody has to do something with all of those resources (good or bad) that still work, technically speaking.

Why not use their own materials, to let them know the things they do wrong, or the things they could do better? I think it’s its own irony.

With vintage materials there is a whole other conversation. They represent time and quality. I’ve had the pleasure of receiving textiles from the 60s and 70s. And only the fact that I could get my hands on them is incredible. That they could still be used. And somebody took the time (and space) to keep them safe. All of those things make me appreciate them even more. They survived time. They had emotional value for somebody. Vintage textiles make me think about our relationship with our objects, their connection with our history and people. Those textiles are extremely powerful in themselves. No matter what I do with them, they have history, which doesn’t usually happen with fast fashion garments.

4. It looks like you’ve had your work in several shows this year. In a world where everything can be shared across the world in an instant on Instagram, what were the benefits of these in-person shows?

I feel like both means of communication has its values.Â

Internet and virtual communication allows me to talk with people around the world. People with the same interests than me. It allows my art to touch more people. To make the conversation global. To experience different reactions that are based on local experiences and ways of living.

Also on Instagram I usually share a section of a work in progress. A small detail of a bigger work. I find it’s a good tool to zoom in on the craft part. I like sharing pictures where you can appreciate each stitch. Zooming in on a stitch is also my way of making the technique the center of attention, and not the whole piece. It’s like showing a stroke of an Impressionist painting.

On the other hand, art shows allow the viewers to interact with an art piece with time. They see, they watch, they feel in an environment that is made for that experience. And they see the whole piece. They can linger on a stitch if they want to.

Personally, on the opening day, I can experience their reactions live. Not by text or emoticons. I can see their faces, their expressions. It’s completely different.Â

Being an artist and an activist, reactions from the public are a big part of my work. If my art doesn’t leave you thinking about some of the issues I try to talk about… I don’t want to say I did something wrong, but almost ha ha. I mean, if that doesn’t happen, my work is not done.

There is a message in my art. A message that should make you think and rethink. It should inspire you. But it is also true that sometimes the intertext is lost. Some of my work are seen as just textile works, when in fact they are textile works specifically made with recycled fabrics as a decision. That sometimes isn’t easy to see. But my artist heart tells me, that’s okay too. I couldn’t stop making, even if nobody gets it ha ha.

Â

“13206 Centimeters of Textile Trash”): upcycled textiles, recycled wood frame

5. Along with embroidering, you also weave, how did you come to connect your craft with activism?Â

Knowing makes all the difference for me. I’m one of those people that once IÂ know something I can’t unknow it. I can’t look the other way. I need to act on that knowledge.

Once I learned about the bad parts of the industry I was supposed to work for, I just couldn’t do it. Not with those rules. For me wasting resources is not a rule. Dyeing fabrics and polluting in the process do not go hand in hand. Making clothes and exploiting workers are not a rule, no matter the circumstances.Â

So I decided to transmit what I learned to others, with the best tools I had, textiles and textile practices. I decided to help and encourage people doing things in this industry with new and better rules. I decided to try to make this subject a part of the conversations of people that do not necessarily talk about them.

I weave, embroider, knit, and sew trying each time to achieve several things: encourage the making with our hands as a mean of expression. Highlight issues about the fashion industry and its destructive practices. Allow my personal needs of making things to have a deeper and more valuable meaning than just my selfishness of making. Yes, and I do strive to change the world. Even if I can’t.

Weaving in particular is a practice so old and so precious. It can be a symbolic way of saying so much. How we connect with others, how we relate. Â It’s a way of relating with ourselves, in the making. With others in the interconnections. And with our world as to what objects we leave behind. I weave fabric, I do not weave thread. I weave that fabric that doesn’t belong to anyone, that nobody wants. I weave from the idea that there is nothing there, because that fabric doesn’t exist because it’s trash. I give life back to what nobody wants. But it’s so transformed that it has value now. It IS again.

I think a lot about the things I make. Why do I make them? What is its purpose? What will happen to it? When I graduated from University I decided I would rather make art that inspires good changes, than products that enlist and encourage practices that are completely wrong for our world.Â