This thought is on my mind today, even though I first shared this photo in June 2013. I’ve been going through some old Flickr photos as I look at various new (and free*) responsive WordPress themes to change this site over to one that is more friendly with the new(ish) Google mandate about mobile-friendly themes and Google search rankings. (If you’re not sure if your website is mobile friendly, you can check it out using Google’s Mobile Friendly Test.) While my site passes the test thanks to the theme I’m currently using (Canvas by WooThemes), I decided this site needed a makeover after creating my freelance site, HelloBetsyGreer.com, and using a beautiful new WordPress theme, Sela.

While we all know I’ve needed to update this site for forever, I hadn’t because I wasn’t sure where I wanted to go with it… more personal? Less personal? Sadly, there’s no sourcebook for what to do when you create an -ism! Or at least one that grows from 2 Google hits to 100,000+, because it wasn’t just me who did that, it was you, too. So what responsibility do I have to you for that? (If you have thoughts or feelings on this, I really, truly want to hear them.)

I think about this question a lot, actually. And each time, I come to the decision that I need to be the person who shares other people’s craftivism (and craftivism-esque) projects, both past and present. Because together, we created an international creative movement! Do you know how entirely rad that is? We made this thing together. I may have put out the first** public flag, but it was you that continued to do so over the past 12 (!!!) years.

In redoing the site, I’m going to make it clearer about people’s projects that have been shared here over time, so that current, curious, and future craftivists can find them. And finally obtain more academic papers to share here, so that students can find this site as more of a resource. Along with that, I’m also going to continue to write my own opinions about the craft world, creativity, and craftivism, because I think there is a place for that, too.

So nothing too drastic, but hopefully an easier site to navigate whether people want to know craftivism’s history or its present form. In the photos that I’ll be using for the site, I’m going to be using some old personal photos, as well as hopefully using the photos of others with attribution. If you have some you’d like to share, please let me know!

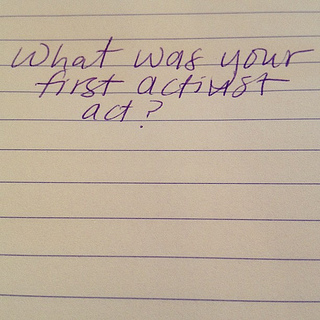

Oh, and my first activist act? Probably stopping eating red meat at 16. A high school frenemy gave a talk in class about the meat industry, and I went home and announced I was no longer eating red meat. While it may not seem like a big deal in 2015, in 1991, it was huge deal, as my family stuck to a meat and 2 sides regimen. In the 22 years since then, I’ve been vegetarian, vegan, and finally settling on pescetarian, even though personally I keep a strict vegetarian kitchen.

Do you remember your first activist act? (Or craftivism act?) If so, do share!

* I’ve used both free and paid themes, and have decided to go with a free theme this time. I’ve used paid themes in the past, and have gotten burned by having to pay various charges after the fact.

** Technically, the Church of Craft put out the very first flag! I first wrote about the connection of craft and activism for a grant, then told my knitting circle what I was doing. One of them came up with the word “craftivism,” so I went home and Googled it, to find that the Church of Craft had previously (this was late 2002) done a craftivism workshop, for which there were 2 Google hits.