I found out about Catherine Hicks’ Hide a Hat and Fight Back over on Instagram via the #craftivism hashtag. If you have craftivism projects, please hashtag them so I can find them more easily!

Next week I’ll be sharing Gather’s “You Belong Here” project, which is needed now more than ever. They’re accepting signs until next week, so get to it!

You can also read more about what Catherine has to say about the project over on Medium.

1. What is your definition of craftivism?

Craftivism is the call for social change through what are considered typical women’s mediums. Craftivism helps craftivists by providing a purposeful outlet for creative energies, which can be directed to increase awareness and encourage social and/or political change.

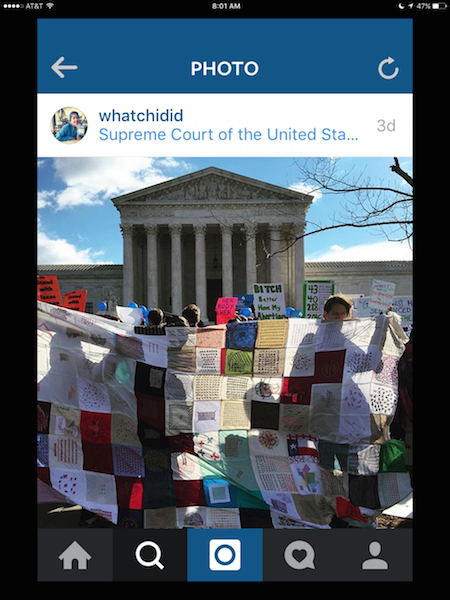

My Art Practice is primarily engaged in Hand Embroidery, and I saw a call last year asking for embroidered squares which were to be sewn together and held in front of the US Supreme Court in conjunction with the Court’s Ruling regarding the closing of Planned Parenthood Clinics in Texas. The project was spearheaded by Nguyen Chi (IG @whatchidid, whatchidid.com/) who was organizing in collaboration with TAC Brooklyn). As a Texan, I was embarrassed and angry about my State’s Policy, so I felt like I had to participate.  So, I made a square (the embroidered hash marks represent Texas women who would lose health services)

What a thrill it was to see my contribution held up in front of the Court!

While working on my square, I did what I always do when starting a new project: I asked YouTube and Netflix to tell me everything that they knew about the subject. I looked at many wonderful clips of videos and documentaries, and learned about the craftivist movement – I learned about Sarah Corbett (of the Craftivist Collective), and followed her internet rabbit trail, which led me to think about issues of social justice.

Because I had done a lot of research on the planned parenthood rulings, I looked up other issues affecting Texas women. I was already particularly concerned about the open carry law, which had just been enacted in Texas. I looked up some gun statistics in the state, and to my shock, I learned that (on average) just under one woman is killed by a domestic partner every day in the Lone Star State. Not all of those deaths are by gunshot, but many women are killed simply because there is easy access to a gun in the house.  The enacting of the Open Carry Legislation was likely to exacerbate this situation. (No Stats yet.)

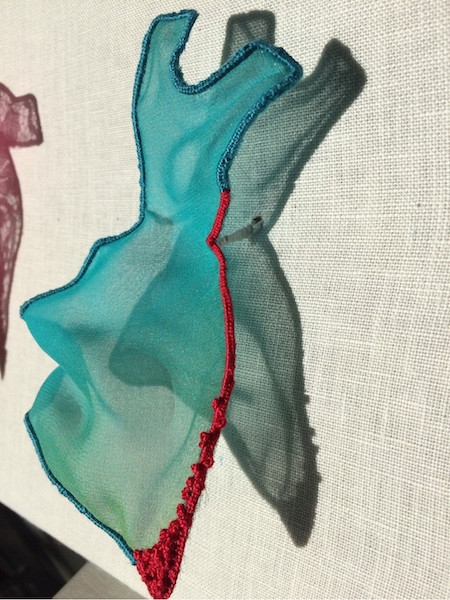

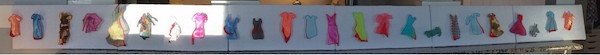

I conceived and began embroidering the BLOWN AWAY project, hoping that I could get a solo show that would viscerally demonstrate what 277 (2013 statistics) dead women looked like. The project was to be made up of a series of interconnected panels (in the manner of the Bayeux Tapestry) that viewers could walk past and think about the mothers, sisters, daughters and grandmothers lost in a single year.

(The photos above are of an individual dress [representing one victim] and a series of panels [representing one month of women murdered  in Texas.)

The project was not accepted anywhere.

So I have dabbled a bit in craftivism; I guess I engage when I get mad enough about something and I don’t feel like any one is listening (a common complaint with our utterly deaf Texas politicians). Even if I haven’t concretely accomplished anything in participating in any craftivist act, I feel better, because at least I am doing something!

Â

2. What is Hide a Hat and Fight Back?

I was very excited about the Women’s March on Washington, and thrilled when I learned that there would be a march in nearby Austin, as well. Scrolling through social media to find more information, I happened upon a call for the Pussyhat Project, asking for hats to be made for Washington marchers.Â

Yarn was immediately purchased. The furious clacking on knitting needles every evening (as my husband and I both ate through miles of pink yarn) got us through the next few weeks, and we found that the knitting relaxed us and gave us a tangible sense of purpose.Â

I got the idea for the Hide a Hat and Fight Back project when we got home on that Saturday night and there was nothing craftivist left to knit. My hands were itching for something useful to do, and I figured that there were other knitters staring at empty needles just like me. In times of trouble my Auntie Ro always said “The cure for anxiety is action!,†so I created an excuse for craftivists to keep knitting as a way of relieving political anxiety.

The tiny hat project in a nutshell:

(couldn’t help myself!)

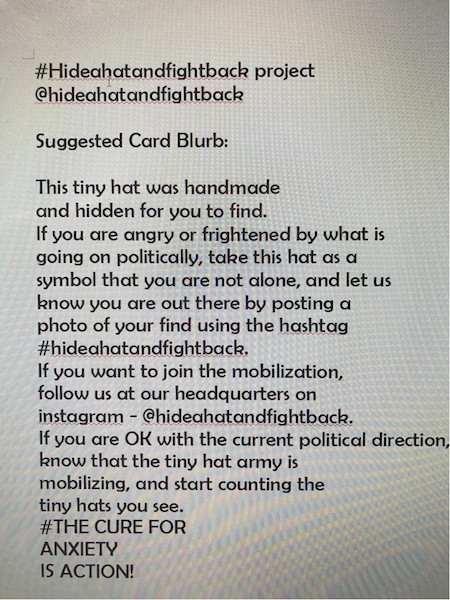

Craftivists are asked to knit, crochet, sew, glue, etc. tiny (fingertip sized ) pink pussy hats. Once completed, the hats will be attached to a printed or hand written card, and the craftivists will document them on social media, then “hide†the cards wherever they want – in a dressing or ladies room, on a public bulletin board, in a taxi or on a bus seat, etc. Of course, they can also be given directly, or mailed to a legislator, or whatever method of distribution the maker favors. Â

The cards will invite finders to post their finds on social media, and will encourage continued political engagement. Finders will be encouraged to join the movement when they post.

3. Why hide them?

Living in a rural community in Texas, everyone almost always assumes I am a conservative. I’m a Lutheran. I sing in my church choir. My kids got good grades, so people make assumptions, thinking that I believe what they believe. Of course I have liberal friends, but we lone star liberal ladies have learned that it is not a good idea to get in a shouting match in an open carry state. We keep a low profile. I know the liberals in my own circle, but I don’t know who the hidden liberals are.Â

The march sort of changed that. I was with 50,000 proudly progressive women, men and children, and we were in the middle of Texas!  I finally found my tribe, and it was thrilling! I had never been in a room with more than 50 Democrats, and, while marching with so many,  I have never had such an overwhelming experience of community.Â

As I was conceiving what the project would be, I knew that it should reach out to my fellow progressives, particularly those living in deep red states. I wanted to remind them (after the news of the march dies down and the hard work begins) that they are NOT alone, and we stand and resist together.  I wanted to give them the thrill of community I felt in Austin. But unless I personally know them,  I don’t have any way to do that in an open way where I live. I took a huge risk just putting up my Hillary yard sign, and I learned to quickly take off or hide my Hillary pin when going into certain restaurants or when running into one of my husband’s clients. The project was my way to keep reminding progressives that, even though we are a shy people, there are a lot of us!

I am acutely aware that Trumpians will likely be offended to find the hats and may be unpleasant in their responses. Inviting that negative energy into my life gave me pause to almost abandon the project, but then I thought it through: If you go through life extremely confident that everyone around you thinks in exactly the same way that you do, it would certainly get your attention if you suddenly and unexpectedly encountered physical evidence that they do not. A few encounters might be easy to dismiss, but what if you saw a dozen or dozens or even one hundred of these things? Your unshakeable belief that you are in an unbeatable majority might start to waver. Many Democrats in my state don’t bother voting because they feel it is hopeless – what if this project flipped that script?

Also, finding something cool is fun!

4. Why tiny hats and not bigger ones?

Because tiny hats are adorable. They can be pinned to your blouse, or hung from your rear view mirror. They can be thrown in a jewelry box or stuffed into your makeup drawer as a daily reminder that the fight isn’t over. They fit on the end of your pencil, or can be slipped on a finger and waved. The kids will want to use them to punctuate when they flip the bird. They don’t have to fit a real head, so fitting issues are not issues. Tiny hats can be made very quickly, so a lot of them can be distributed in a short amount of time.  They can fit in a craftivist’s purse or pocket, in case of travel into  an unfriendly area. They can be made while waiting in a school pick up line, or while sitting at the doctor’s office, or while on public transit. Big balls of yarn and needles are not required, as travel equipment is purse sized. Tiny hats are a symbol of the larger hats, and, in turn, a symbol, a reminder, a requerdo of the larger movement. And did I mention that they are adorable? That said, if people want to make bigger hats, then make bigger hats. If they want to make tinier hats, then God Bless them, and I wish I could see as well as they do. The project is my gift to the community; what they do with that gift is up to them.

5. What is your goal for this project?

Right now, I just want to get the word out and get people mobilized, activated and engaged with the curative power of having something to do. I want them to fill out the urgently needed political postcards, make the calls, and engage in the post march call to action, but I want them to also be able to do something where their focus shifts to the non thinking headspace of:  “needle behind, loop forward, correct tension, transfer the stitch, repeat.â€Â I want them to be able to turn their mind off and on through a radical act of crafting. Selfishly, I want to see what they make. Already I have been sent sketches, suggestions and sighs of relief. That was my biggest thrill today.Â

The secondary goal is:

What’s the reaction? I have no idea if I have opened (as we say in Texas) a big can of whoop ass on myself. If I have, then at least I have taken a stand. Texas women used to do that, and I know a lot of us still carry that gene. I want people to post about how they found their tiny hats and how it made them feel. Did the hat meet them on a bad day? Did the hat bring them hope? Will Fox News be quoted? Will Steve Bannon curse?

Like with my two boys just a few years ago, my job is to send the project out into the world. What happens next is my concern, but it is not anything I really have control over. That’s the risky part of Art Making.

What is my dream result?

World Peace. A Single Payer Health Care System. Reversal of Climate Change. A well supported public education system that continues through a Bachelor’s degree. A legislature that is consistently 50 percent female.  The abolition of gerrymandering and Citizen’s United. A complete rethink of the electoral college. Passage of the ERA.  Justice for All regardless of skin color or ethnicity.  A modern energy system that is not dependent on oil. Equal Pay. An end to income inequality. An engaged and factually informed electorate. The Right to Marry and the Right to Choose. Well funded arts programs. A basic income for all. Yada Yada Yada. I would settle, though, for a progressive legislature and a President Warren.