Sweetheart cushions. Not exactly craftivism… but, as they were helpful projects that connected soldiers and sailors to their loved ones, I’m going to say they are craftivism adjacent. Projects like these can be extraordinarily helpful when dealing with trauma and loss, because you’re thinking of designs and loved ones and things beyond what is happening all around you. Interestingly, some websites say that these pin cushions were made by women and sent to the soldiers and sailors, when, in fact, it was the men who made them instead.

I’ve been digging a bit into how they started and come up a bit spare, so if you know anything, please let me know! Additionally, I’ve started doing historical posts again, because I’m ramping up my own research for various things. Once I get to 48 of them, I’m going to retroactively number the posts so that 48 Acts of Historical Craftivism will live here in full. Due to dealing with my own trauma issues, putting up a research post every week last year wasn’t feasible. That being said, if you’re ever putting out work to the public, be kind to yourself if it doesn’t work. If it’s important, you will come back to it again. Sometimes we’re not fully ready to do a project, so it’s best to put it down for a bit and take care of our selves first.

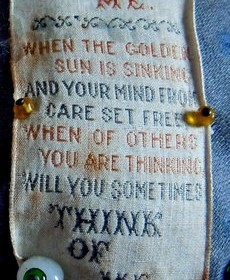

This post takes you a bit down the rabbit hole of textile research, as it gets confusing and all of a sudden you find yourself looking at photos of Queen Victoria and see if they match a photo in a pin cushion (below), reading information that doesn’t add up, finding completely different theories than any other text mentions, and other fun stuff. So, welcome to a post with lovely photos that also explores how one explains something that no one seems to know a whole lot about. Be sure to click on the photos to see them in real size. Additionally, none of these photos are mine. They are either from the link in the related text or from Pinterest.

So, how did these sweetheart pin cushions come about? A lovely piece in Slate about them suggests:

“Nancy Mambi, librarian at the Textile Center in Minneapolis, Minn., which mounted an exhibit featuring sweetheart pincushions last year, says that the tradition began in the nineteenth century with Queen Victoria. The Queen was an amateur practitioner of textile arts, who thought that soldiers might find quilting or needlepoint a great distraction while far from home.“

Most of the ones with dates that I found coordinate with WWI, although some text also noted that pin cushions were also sent by soldiers and sailors during the Boer War. So, a little look at history, the first Boer War (and actually, if you were Boer, you would call these wars the Wars of Independence, learn all about it here) was from 1800-1801, the second Boer War was from 1899-1902, and Queen Victoria was queen from 1837-1901.

I did find a photo of one marked 1896, but I’m not exactly sure what war it was for. However, it does have an amazing tassel fringe, so it simply must be shared:

I don’t know about you, but this leaves me confused about why these pin cushions were still being made during WWI (1914-1918) with photos of Queen Victoria, or at least it looks like Queen Victoria over Alexandra, which the eBay listing seems to think is on there:

And it definitely does not explain who this dude is (but I *so* want to know!):

Also, this search led me to discover hussif (“housewife”) rolls, which were made by women for their soldier or sailor. Check them out here.

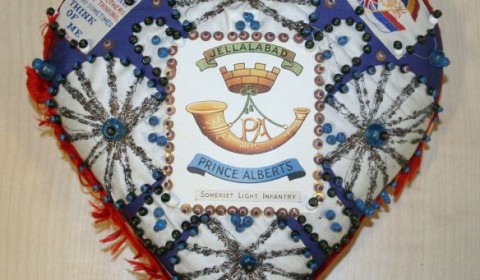

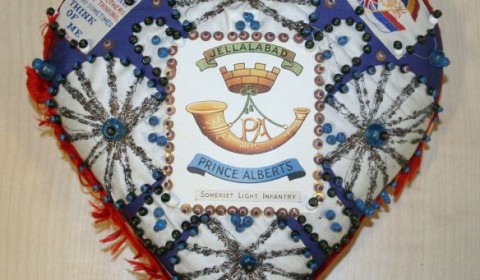

A sweetheart pin cushion from a soldier in The Royal Norfolk Regiment owned by the Museum of Technology. The entry for this cushion starts with: “pin cushions, were a very common memento sent home by the troops to their loved ones during WW1. As with this one, they often incorporate the name of the soldier’s unit – here the insignia, of Britannia and the regiment’s colours can be seen,” and ends with a description of a battle the regiment endured if you want to click over and read more.

So, these pin cushions feature a variety of cool things that I learned about along the way, such as cigarette silks, which came in cigarette packets:

“A Cigarette Silk is a small piece of printed (or woven) satin (almost never silk) given away free inside yesteryear’s cigarette packets as a marketing ploy. There was an assortment of subject matter and they had silk ‘issues’ depicting animals, flowers, motor cars, and railways. The list was endless, but with the outbreak of World War I; Military Badges, Regimental Colours, Uniforms, Medals, Flags, and War Heroes became all the rage, especially with male smokers.”

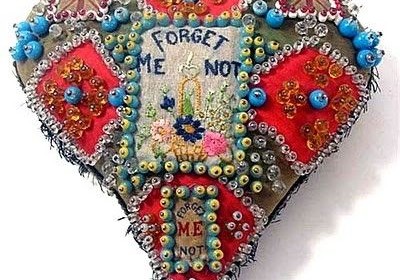

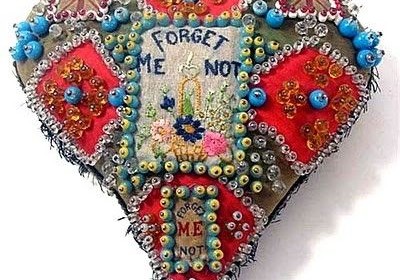

Additionally, all those beads you see were put individually on straight pins, which were then stuck in the cushions (that were stuffed with things like sawdust) to create various designs. I like the masculine element it gives these sweet pincushions, because maybe I’ve missed something, but I’ve never seen a women’s version of this technique. Who knows if the technique was created because of what they had lying around or was by design? (No, really, I want to know.)

There are whole boards on Pinterest dedicated to these pincushions, like this one, this one, this one (which has some contemporary versions), and this one. A lot of the photos are from old eBay auctions.

The artist Janet Haigh has photos of some good ones here, too. Additionally, she has some photos of a mending job done on an original WWI pin cushion!

If you click on the photo above, you’ll see that the text for this Pinterest pin says that these pincushions were “often made from kits given to soldiers recovering from their injuries.” The text for the photo below says the same thing. The photo is taken from the Imperial War Museum’s collection.

The cigarette silk above I saw on several different examples, and in its linked post, found another theory about the pin cushions’ origins.

Most pin cushions, like the one below, were offered in several different places on the internet, with no information at all about them.

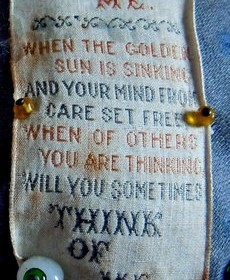

Although there was the occasional luck with text, like the post that included the following photo and text:

As a teenager I worked in an antiques shop in Allerton, near Wedmore, and Dorcas Elliott who ran it gave me a First World War sweetheart pin cushion. What I did not understand was that it had been made by a man.Â

The tradition started in the 19th century when Queen Victoria decided that soldiers might find quilting or needlepoint a great distraction while far from home . Soldiers made beaded pincushions during the Boer War from cloth taken from wool uniforms. Decorative pincushions became very popular during the First World War when injured soldiers and sailors made thousands of pincushions to express their love for home and country.Â

. Soldiers made beaded pincushions during the Boer War from cloth taken from wool uniforms. Decorative pincushions became very popular during the First World War when injured soldiers and sailors made thousands of pincushions to express their love for home and country.Â

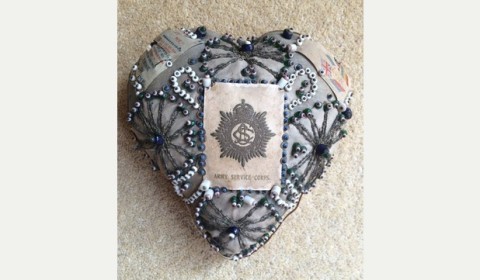

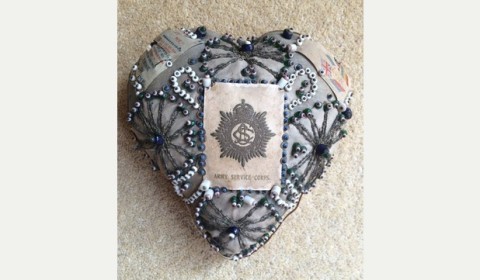

The Imperial War Museum says that some of the cushions were made out of commercially sold kits, while other examples were sewn using feed sacks and scrounged thread. And mine, I think, is one made from a kit, which was available to serving soldiers and sailors.Â

As you can see he was a member of the Army Service Corps, which provided backroom services including administration. It is now part of the Royal Logistic Corps.Â

And since we’re speaking of love tokens and being far away from ones you love, I also discovered that there are convict love tokens. Whoa. As well as a period of time where pillows for babies were embroidered with phrases like “Welcome Little Stranger,” which is just about perfect.

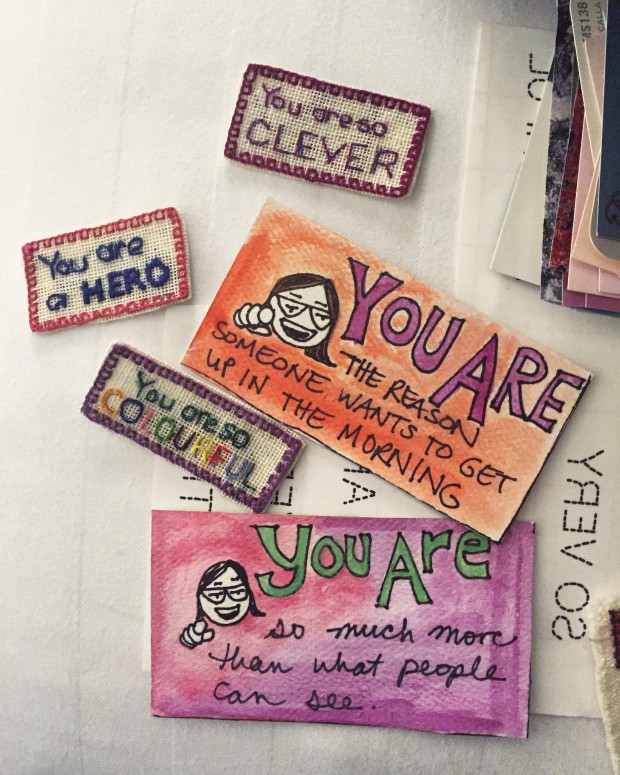

I also found the photos below, which are notable given that they are made during the same period, with similar messages. The post they came from added the following accompanying text:

These pillowy treasures got us thinking about even older Canadiana, specifically Haudenosaunee beadwork purses and pincushions. These beautiful souvenirs began to appear not long after Loyalist Mohawk troups resettled in Canada after the American Revolutionary War. Haudenosaunee from both sides of the border found themselves living on reservations, cut off from their traditional land and way of life. The communities sought out new ways to make a living, and the women began making souvenir beadwork.

Most of it was sold around Niagara Falls but examples that bear the names of towns like Toronto and Montreal can also be found. Contemporary sewers still create stunning beadwork, but we have a soft spot for the sentimental Victorian versions.